Since late last year, air logistics executives have engaged in wishful thinking that the protracted downturn in shipping demand would start to recover after the first quarter and build through the year once retailers cleared out excess inventories. That rosy scenario is fading.

Worsening indicators suggest the international freight recession hasn’t hit bottom and that the best outcome air cargo providers can hope for until October — typically the peak season for goods movement — is halting the slide.

The growing risk of recession, ongoing inventory overhangs and injection of additional capacity as airlines return passenger aircraft to post-pandemic summer service means bookings and rates will continue to languish for months, according to recent data and industry analysts.

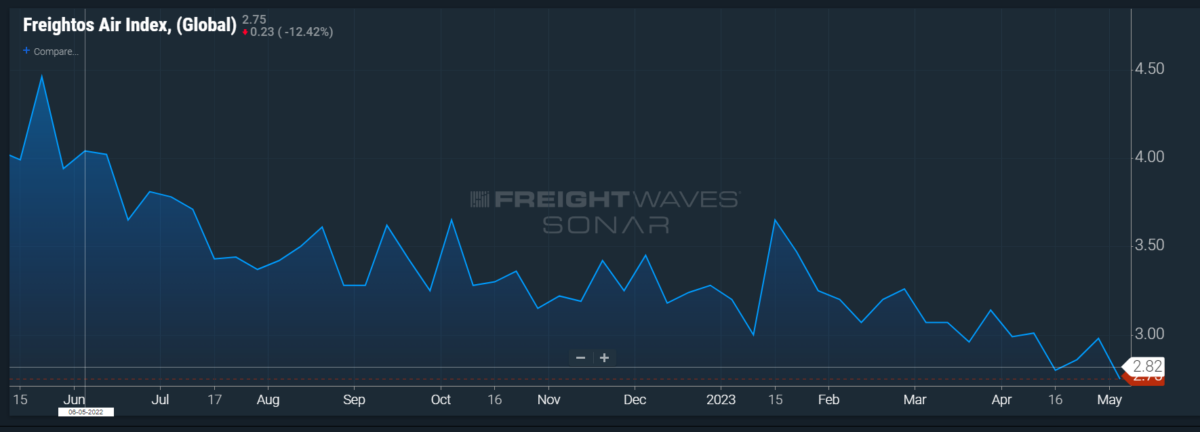

Global air cargo volumes are currently down between 8% to 10% from last year’s elevated levels, with rates tumbling more than 40%. The rate of volume decline has slowed since December, taking more of a gradual stair-step descent in which tonnage and rate temporarily firm before dipping again. But temporary signs of stabilization likely have more to do with easier 2022 comparisons when the Chinese economy was still closed down, rather than with any demand improvement.

Market intelligence firm Xeneta reported that airfreight volume in April shrank 4% from the prior year, backsliding from the 3% decline in March. Trailing data for March from the International Air Transport Association showed global demand fell 7.7% in March and that shipment levels were 8% below the 2019 benchmark.

Chemicals and lifestyle products, including apparel, are leading the decline, said ocean logistics integrator Maersk (DXE: MAERB) in its quarterly report last week.

The downward trend has carried into May, with researcher WorldACD reporting a 10% decline in tonnage from the prior week due, in part, to the May 1 holiday in many countries.

Logistics experts say any improvement in air cargo demand through early 2024 will barely be perceptible.

“Looking forward, we see little hope for renewed strength in air cargo rates absent a demand catalyst later this year, even if it’s more seasonal than structural,” wrote Bascome Majors, a freight transportation analyst at Susquehanna International Group, in a recent client note.

Two conditions are influencing the change in sentiment about airfreight demand: Anemic manufacturing activity and a growing realization that many companies are deferring broad inventory replenishment because of concerns about consumer confidence as the global economy continues to decelerate.

Economic clouds darken

In an interview with Bloomberg TV last week, Evercore Chairman Ed Heyman predicted a recession will begin this summer as the aggressive monetary tightening policy of the Federal Reserve and other central banks ripples through the economy. Higher interest rates and recent bank failures are drying up the money supply businesses use to grow.

And even though major economies are holding up better than anticipated at the start of the year due to a warm winter, falling energy prices and China’s reopening from a COVID cocoon, their strength is concentrated in the service sector. People are buying fewer goods than two years ago when the pandemic limited activity outside the home.

Global manufacturing is actually contracting due to the slow destocking process and low confidence in future consumer demand. The Purchasing Managers Index for manufacturing, a leading indicator for air shipping, remains in negative territory for the largest economies. China’s manufacturing sector even contracted in April and new export orders at the global level are also underwater.

The decline in global goods trade accelerated in February to 2.6%. The World Trade Organization recently lowered its 2023 forecast for merchandise trade growth to 1.7% after 2.7% growth in 2022, citing the effects of the war in Ukraine, stubbornly high inflation and turmoil in the financial sector.

A good proxy for air cargo is ocean freight. The National Retail Federation is projecting a larger decline in U.S. imports in the first half of the year than it forecast in April. The trade association estimates that container volumes for the six-month period will be nearly 23% lower than a year ago, when volumes were still unusually strong. Third-quarter box volumes are expected to be 7.2% below last year’s level.

“Our view is that imports will remain below recent levels until inflation rates and inventory surpluses are reduced,” it said.

The latest ocean container bookings data on FreightWaves’ SONAR platform for U.S.-bound container volumes departing China continue to exhibit the overall weakness in U.S. import demand, with any chances of a second-half rebound getting increasingly unlikely. As in air, ocean shipments from China to the U.S. moved up a notch in April, but the small bump in volumes is not likely to become a sustained trend, according to a FreightWaves’ analysis of Chinese manufacturing and shipping data.

The consensus within retail and manufacturing circles is that inventory levels are normalizing and bookings will pick up soon, but some caution against over relying on inventory data for forecasts.

Half of respondents polled by logistics provider Flexport during a webinar last week said they have all the products they need, while 30% said they had too much. In February, the number of companies that had too much stock was higher. While many companies may have too much inventory in one category, they might not have enough products needed for the holiday season. The question is whether that readiness to place orders translates into an intense peak season or just an upward tick from the current lows.

Many corporate leaders have recently said they are not reflexively restocking yet because of concern consumers could pull back on spending if economic conditions worsen.

“While we agree that it feels like we are near a trough, and inventory levels are nearing an inflection point relative to where they’ve been in history, most of the calls for an actual demand recovery seem speculative, and shipper forecasting for capacity needs has been getting less accurate, in our view,” wrote Bruce Chan, senior logistics analyst at Stifel investment bank, in a monthly commentary for the Baltic Airfreight Index newsletter.

Maersk executives said they don’t expect the inventory clearance process to be complete until some point in the second half of the year, but they don’t have a clear sense when exactly shipments will pick up.

The challenging environment means airfreight demand is now expected to be flat, at best, this year, said Maersk, which also operates a cargo airline.

And the greatest risk to air cargo, and trade in general, likely is the U.S. debt ceiling crisis. If the U.S. legislature doesn’t raise the allowable outstanding federal debt the government will default on bills it owes in early June, which is raising fears of an economic rupture, chaos in financial markets, a loss of consumer confidence and a deep recession.

The rising number of negative economic forces could mean the air cargo sector will have a second consecutive year without a fall peak-season surge. It’s early to make that call, but not something logisticians can rule out.

Freighter Fallout

Slumping demand is leading many all-cargo and express operators to reduce capacity. There is a strong correlation between cargo flight hours and freight demand.

Dedicated freighter activity fell 5.2% in April from last year — more than the contraction in March and February — primarily due to pullbacks in North America and Asia, according to analysis by equity analyst Fadi Chamoun at BMO Capital Markets. Notably, April represented the steepest decline in flight hours over the past two years, on a seasonally adjusted basis.

At UPS (NYSE: UPS), a 6.2% decline in international volumes contributed to a 22% drop in operating income during the first quarter. The company said it cut aircraft utilization by 14% in Asia and will reduce flying even more during the second quarter. It is also pushing deferred domestic deliveries onto overnight planes to maximize available space and reduce daytime flying. FedEx (NYSE: FDX) is parking planes, moving up the timetable for retiring older aircraft and reducing flight hours 10%. And Cargojet (TSX: CJT) indefinitely postponed plans to convert four Boeing 777 aircraft into freighters.

“Indications are that demand is softer than we would have anticipated even back in March when we were reviewing our Q4 results,” Chief Strategy Officer James Porteous said during Cargojet’s May 1 earnings presentation.

Cargo revenues for passenger airlines were about 30% to 40% lower during the first quarter than the same period last year. Logistics powerhouses Kuehne+Nagel and DSV said their air volumes declined 17% and 20%, respectively, during the first three months.

The drop-off in air cargo is across the board, including premium products carriers covet because they require special service that brings higher margins.

Demand for pharmaceuticals is down 29% year over year, most likely because there is less need to ship COVID vaccines, Accenture said in a recent report. Demand in other key sectors is also flagging, with fashion down 18%, high tech down 12% and automotive down 11%.

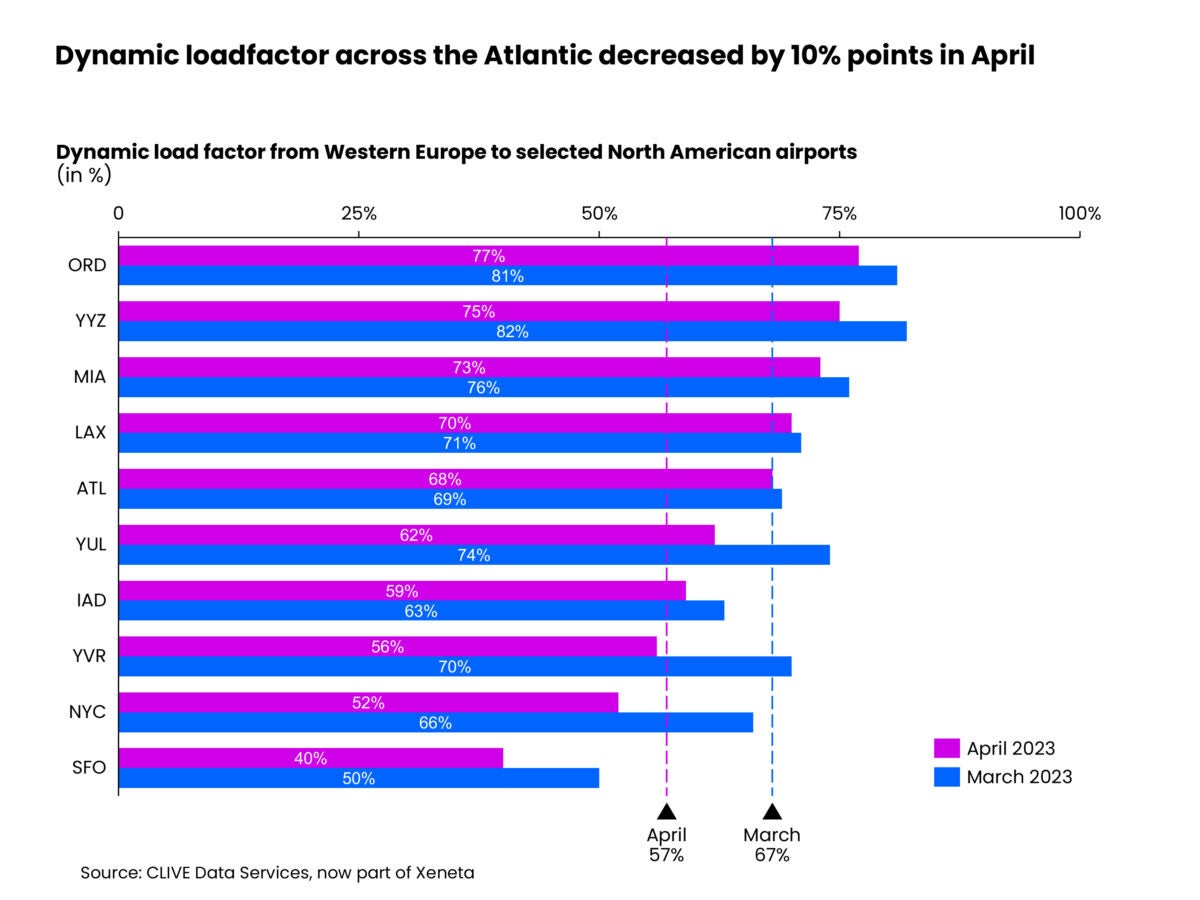

Meanwhile, more capacity is pouring into the system as the recovery in passenger travel adds cargo space on key trade corridors. Available cargo space increased 7% in April, according to Xeneta.

Rising capacity and falling demand translate into planes being less full, which in turn is pressuring freight rates. Xeneta said cargo capacity increased 7% month over month in April and 16% from a year ago, with aircraft fill-rates falling 5 points to 57%. IATA’s data shows cargo capacity grew 10% in March versus 2022.

The influx of passenger flights has had a major impact on the air cargo market from Europe to North America. Spot rates on that lane fell 12% in recent weeks as cargo capacity jumped 26% from last year and load efficiency deteriorated by 10 points.

Passenger carriers in Asia are also ramping up service following the recent reopening of China and the lifting of other COVID travel restrictions in the region.

The U.S. Department of Transportation recently allowed a 50% increase in weekly frequency for Chinese passenger airlines. Chinese carriers are now able to operate 12 weekly round-trip flights to U.S. destinations, matching the number of flights allowed into China by U.S. carriers. The number of flights pales in comparison to what was allowed before the COVID crisis.

After re-establishing a San Francisco-to-Hong Kong route in March, United Airlines announced an increase to 12 weekly flights in August and another two by the end of October flown by large Boeing 777s.

According to the Seabury consultancy, freighter capacity fell 14% in April while passenger belly capacity increased 23%.

Rates from China to Northern Europe are about $3.43/kg, more than 50% below their level a year ago, the Freightos Air Index shows. The price to ship by air from Shanghai to North America declined 11% in early May to $4.46, the lowest absolute rate for that route since the airfreight surge in March 2020 when emergency airlifts were conducted at the start of the pandemic to deliver face masks and other medical equipment.

The increased transport supply in passenger networks and smoothing of ocean congestion is hurting all-cargo operators as shippers trade down from premium freight to slower modes to save money.

Although rates are still holding above pre-pandemic levels, most of the difference is for surcharges to help airlines offset elevated fuel prices.

“If demand softness persists and belly capacity continues to recover, we would expect further rate declines as we move through the remainder of the year,” said Stifel’s Chan.

(Correction: Bascome Majors name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.)

Click here for more FreightWaves and American Shipper articles by Eric Kulisch.

Sign up for the weekly American Shipper Air newsletter here.

Contact: [email protected]

RECOMMENDED READING:

UPS downshifts flight activity as volumes deteriorate

FedEx says air network restructuring to save $700M annually

American Airlines’ cargo revenue shrinks 38% in 1st quarter

Air cargo operators still feel ‘hangover from the 2021 party’